In placid hours well-pleased we dream

Of many a brave unbodied scheme.

But form to lend, pulsed life create,

What unlike things must meet and mate:

A flame to melt--a wind to freeze;

Sad patience--joyous energies;

Humility--yet pride and scorn;

Instinct and study; love and hate;

Audacity--reverence. These must mate,

And fuse with Jacob's mystic heart,

To wrestle with the angel—Art.

“Art” by Herman Melville

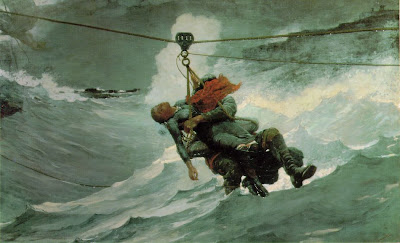

Herman Melville (in an 1870 portrait above) wrestled “with the angel—Art” throughout his life, in all its forms. In Melville: The Making of the Poet, Hershel Parker, perhaps the finest Melville scholar alive, first tackles the misconception that Melville was almost exclusively a novelist and then documents the amazing depth of Melville’s aesthetic voyage into the heart of poetics as well as the heart of visual artistry.

The popular idea of Melville as primarily a novelist owes much to the cultural power of Moby-Dick, so that misconception is understandable. What’s hard to fathom is the staying power of that misconception amongst some Melville scholars, many of whom have attacked Parker in reviews for his stance on the importance of poetry in Melville oeuvre. Early scholars could claim ignorance thanks to the fact that many of the poetry books from Melville’s library containing his marginalia didn’t come to light until the last several decades. But even that mountain of evidence, which Parker aptly and insightfully presents, fails to convince many. I personally find it befuddling having read most of Melville’s poetry and a great deal of the scholarship on it, which is a sadly small body of work. I even made my own small contribution to that field in my MA thesis, inspired by an article by Thomas Heffernan on Melville’s marginalia in his copy of the works of William Wordsworth. (See more on that below.)

What intrigued me now in Parker’s book was his coverage of Melville’s approach to the visual arts in his poetry. Even Melville’s earliest critics recognized the visual component of his novels. In 1850, one critic drew comparisons between Melville’s writing in White-Jacket and the works of J.M.W. Turner: “Mr. Melville stands as far apart from any past or present marine painter in pen and ink as Turner does from the magnificent artist vilipended by Mr. Ruskin for Turner’s sake—Vandevelde. We cannot recall another novelist or sketcher who has given the poetry of the Ship—her voyages and her crew—in a manner at all resembling his.” Melville makes this connection to painting even more obvious in his extended passages of pseudo art criticism in Moby-Dick (i.e., the nebulous painting on the wall that Ishmael encounters in the Inn before shipping off) and in the central role that portraits play in Pierre. In his poetry, however, Melville made that connection even more explicit, referring to works of art by Elihu Vedder and others as the specific source of poetic inspiration.

Parker, however, concentrates on the making of the poet rather than the poetry (optimistically adding that “Melville the Poet and Melville as Poet may not long remain unwritten”; perhaps Parker himself will do the writing). Parker dates Melville’s serious analysis of visual aesthetic theory to his purchase of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Painters in 1862. Melville “quickly applied to the art of poetry what he read about painting and sculpture,” Parker writes. “Notably, Vasari helped clarify for him the distinction between expression and form, or design,” Parker continues. “Melville was struck by Leonardo da Vinci’s deliberately not manifesting the greatest ‘clearness of forms’ but emphasizing ‘the great foundation of all, design’; clarity of design he saw as more important than coloring (the painterly equivalent of literary ‘expression’).” The Italian Renaissance concept of disegno or design—the idea that can be realized in multiple media yet never exhausted by any single medium—appeals to Melville in his exhaustive approach to ideas. Just as he could circle around the concept of the whiteness of the whale ad infinitum in Moby-Dick, Melville believed he could perform the same act through poetry, perhaps even better than in prose.

The second great art theorist influencing Melville is John Ruskin. Melville purchases Modern Painters no earlier than 1865, but may have borrowed a friend’s copy as early as 1862. Notes on Ruskin’s text appear on the flyleaf of his copy of Vasari’s Lives. One note transcribes Ruskin’s belief in the primacy of expression, a main point of his defense of Turner: “Expression—Get in as much as you can.—/ Finish is completeness, fullness, not polish.—“ Following this dictum as well as Ruskin’s advice to pursue “noble subjects,” Melville reinforced and gave definition to his personal aesthetic and found the strength to attempt new projects in verse rather than prose. In following Ruskin (and, by extension, Wordsworth, the most Turneresque of poets), Melville swims against the popular literary tide. “Melville’s decision in many of his poems not to aim for what was then being called Dutch realism or Pre-Raphaelite realism was not designed to win him the widest audience,” Parker writes, “but it was a conscious literary choice made under the influence of” Wordsworth, who stressed “treating things as they appeared to him, as they seemed to exist to his senses and passions.” Ruth Bernard Yeazell’s Art of the Everyday: Dutch Painting and the Realist Novel (my review of that book here) traces the trajectory of “Dutch realism” throughout the nineteenth century, from George Eliot’s battle with Ruskin to Marcel Proust’s unique embracing of that aesthetic. Melville adopts in his poetry Ruskin’s resistance to “Dutch realism” as defined by the popular idea of Golden Age Dutch painting at the cost of falling out of step with contemporary novelists and the taste of the public at large. It would be interesting to read someone take Yeazell’s thesis and apply it to the poetry of Melville and other late Victorians such as Robert Browning and Tennyson.

Parker remains the dean of Melville studies in America, yet amazingly fights an uphill battle against those who downplay the role of poetry in Melville’s life as an artist. Perhaps even more importantly than that corrective, Parker’s analysis of the role of visual art theory in Melville’s poetry opens up a whole new door on the artist as more than just a novelist. In Parker’s exposition, Melville becomes a da Vinci-esque creator of disegno, in which fullness is all and ideas ripen into endless varieties of strange and wonderful fruit. Like Melville with the “angel—Art,” Parker has a great deal of wrestling left, but in Melville: The Making of the Poet, he’s won the first round.

[Many thanks to Northwestern University Press for providing me with a review copy of Hershel Parker’s Melville: The Making of the Poet.]

[BONUS BOB: In my previous life as a literary pseudo-scholar, I published a piece in Romanticism on the Net (now known as Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net) discussing the influence of Wordsworth’s poetry about the French Revolution on Melville’s poetry about the American Civil War. If you have an interest in Melville, Wordsworth, and/or poetical treatments of sociopolitical events, enjoy! If you just can’t get to sleep, it’ll do the trick in a jiffy.]

,+1864.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)