When the stars threw down their spears,

When the stars threw down their spears,And watered heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

From “The Tyger” by William Blake

Two hundred and fifty years ago on this date, William Blake, one of the greatest figures in British art and literature, was born. Perhaps no other artist combined such great talent in both art and poetry and such a capacity to combine both those fields so seamlessly. His illuminations of his own poetry, such as The Tyger (above, from 1794), add a whole other dimension to his art. Whole libraries of criticism have been written on Blake, so I can add only my humble piece to the pile. (If you’re looking for a place to begin, Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry and Harold Bloom’s Blake’s Apocalypse remain my favorites.) To take The Tyger as an example of Blake’s symbiotic art of words and imagery, just look at the tiger at the bottom of the page. Blake’s tiger looks more friendly than fearful, smiling as if he had just escaped from a painting by Edward Hicks. Blake’s benign beast belies the idea of nature as “evil.” Nature just is, with good and bad defined by human reason and superimposed on the natural processes both tigers and lambs follow. The power of Blake rests in his ability to see the world with fresh eyes. As Blake once said, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” (Jim Morrison took those words, and many others by Blake, to heart many years later.)

+1794.jpg)

Blake’s spirituality earned him a reputation as a madman during his life. When a friend found Blake talking to a tree, he asked him if he was actually talking to the tree. “Of course not,” Blake replied. “I’m speaking with the angel in the tree.” However, Blake never blinded himself to the possibilities of science. Isaac Newton became one of his favorite subjects. In The Ancient of Days (God as an Architect) (above, from 1794), God himself assumes the role of a man of science, taking the measure of the universe he created. Just as there is always a balance between poetry and painting in Blake’s vision, there is always a balance between reason and imagination—a continual back and forth where neither side dominates for risk of losing the benefits of the other. Blake’s art intoxicates you when you first encounter his poetry or his imagery. Then it overwhelms you with his complexity. Because of this difficulty, a select handful of followers kept Blake’s memory alive and rescued it from the very real threat of obscurity.

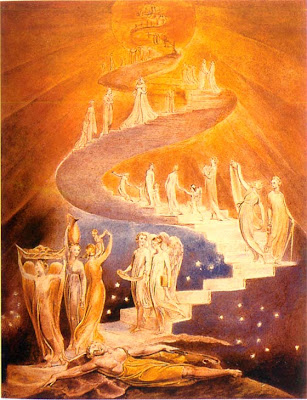

Among those followers was the painter-poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who helped see the first biography of Blake into publication in 1863 after the death of the author, Alexander Gilchrist. Since those early efforts, from the Pre-Raphaelites on, each generation has come to Blake and found something that speaks to it. Images such as Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder (above, from 1800) bring the stories of the Bible to life like few others. Blake’s own Christianity was highly unorthodox, which actually adds to the freshness and appeal of his religious works. The PMA owns a wonderful little Nativity scene by Blake in which the Baby Jesus literally flies out of the Virgin Mary’s womb. It used to hang across from J.M.W. Turner’s The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, October 16, 1834, my favorite work in the PMA’s entire collection. I always would make a point of looking at that tiny Blake after getting my full Turner fix. I’m pretty sure that Blake and Turner never met, but I’d love to have sat in on that conversation.

1 comment:

I have to think a conversation with Blake must be a weird one, but I'd like to sit in on it, too.

Post a Comment