William Blake, London, Plate 36 from Songs of Innocence and Experience, Copy B, 1974; Relief etching in orange and black, colored by Blake; 110 x 69 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

William Blake, London, Plate 36 from Songs of Innocence and Experience, Copy B, 1974; Relief etching in orange and black, colored by Blake; 110 x 69 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British MuseumI wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant's cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear.

How the Chimney-sweeper's cry

Every black'ning Church appalls;

And the hapless Soldier's sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro' midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlot's curse

Blasts the new born Infant's tear,

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

“London” (1794) by

William BlakeTo celebrate William Blake’s 250th birthday and the 200th anniversary of the British Transatlantic slave trade, the

British Museum and the

Hayward Gallery join forces to present

Mind-forg’d Manacles: William Blake and Slavery, currently at the

Burrell Collection at Glasgow. In the exhibit

book of the same name, Blake scholar David Bindman analyzes Blake’s response to slavery in his painting and poetry not only specifically in the form of the enslavement of Africans, but also universally in the enslaved condition Blake saw in his native England and all humanity. Darryl Pinckney, novelist and scholar of African-American literature, adds valuable context in his essay, “’In My Original Free African State’,” which tells the story of the struggles of

Olaudah Equiano, the first black person to write an autobiography in English completely without assistance. Through this exhibition and catalogue, Blake’s response to the horrors of the slave trade takes its rightful place in that social dialogue as well as stands out in the uniqueness and transcendence of where Blake eventually took that response.

Debate on the slave trade filled the air of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century England. Abolitionists

Granville Sharp,

Thomas Clarkson, and

William Wilberforce gathered support and pushed legislation to end the practice of buying and selling human beings. Blake’s fellow

Romantic poet

Samuel Taylor Coleridge preached sermons on the evils of the trade as a minister in Bristol. Blake’s own first-hand introduction to the horrors of slavery came in the form of a 1796 commission to do engravings based on the drawings (now lost) by

John Gabriel Stedman for his autobiography recounting his years as a mercenary soldier in the Dutch colony of Surinam, where slavery flourished in all its cruelty. Blake’s engravings show many of the punishments inflicted upon slaves, including torturous “stress positions” designed to break the body and spirit. One poor victim hangs from the gallows by his ribs as a slave ship floats upon the distant horizon and bleached bones and skulls appear scattered in the foreground.

Before Blake’s encounter with Stedman, however, he had long incorporated the rhetoric of slavery into his art and poetry. The poem “London” (the illustration for which is above) from his

Songs of Experience speaks of the “mind-forg’d manacles” of the world around him. “Blake was not unusual in his time in using slavery as a metaphor and figure of speech,” Bindman writes, “but his use of the word is exceptional in being tied to the physical reality of slavery.” Whereas another poet such as

Percy Bysshe Shelley could write of

Prometheus Unbound and use the rhetoric of slavery as a metaphor for a whole state of mind, Blake’s personal knowledge of the peculiar institution brings a concrete power that adds a whole new dimension.

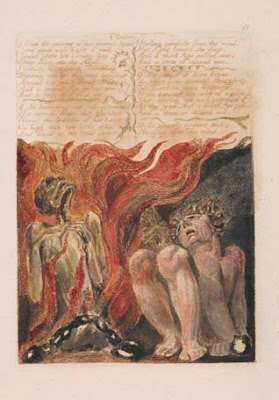

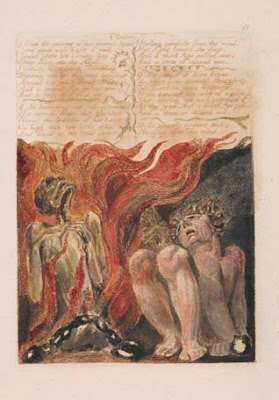

William Blake, Urizen in Chains, Plate 20 from The First Book of Urizen, Copy D, 1794. Color-printed relief etching with hand coloring; 157 x 100 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

William Blake, Urizen in Chains, Plate 20 from The First Book of Urizen, Copy D, 1794. Color-printed relief etching with hand coloring; 157 x 100 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British MuseumBindman dives headfirst into the murky waters of Blake’s system of the “prophetic books” and clears the way for the casual reader to see the beauty and artistry of Blake’s use of the concept of slavery extended to all forms of oppression. Blake’s

Urizen in Chains (above) shows the enslaved Urizen, whom Bindman succinctly calls “the presiding deity of the material world, who represents the domination of rationality unmitigated by the spirit, and all the powers that enslave man’s soul and body.” Copying the body language and actual physical bonds of slavery, Blake imposes that reality on his fictional creation to serve a higher purpose—the revelation of the world itself as a prison. Blake imprisons the imprisoner Urizen here, however, to symbolize how those who enslave the minds of others also enslave their own.

Kara Walker, the African-American artist currently

exhibiting at

The Whitney Museum, centers much of her work on this “endless conundrum” of the effects of slavery on both the master and the slave. (My review of Walker's exhibition is

here.) Walker benefits from much post-modern philosophy on the subject, whereas Blake’s intuitive grasp of that conundrum shows just how psychologically perceptive he could be and how “modern” he remains.

William Blake, Illustrations to Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, 1796-97, Night VIII, titlepage Virtue’s Apology: or the Man of the World Answer’d; Pen and watercolor; 420 x 325 mm (approx.); Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

William Blake, Illustrations to Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, 1796-97, Night VIII, titlepage Virtue’s Apology: or the Man of the World Answer’d; Pen and watercolor; 420 x 325 mm (approx.); Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

In the illustrated title page to Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (above), Blake places the heads of the great oppressors of the mind—a cardinal, pope, judge, and soldier—upon the body of the great beast of Revelation as it’s ridden by the Whore of Babylon. Never one to avoid fights, Blake targets the church and state as the greatest barriers to freedom, both physical and mental. “Priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,/ And binding with briars my joys and desires,” Blake writes in “The Garden of Love.” As Bindman concludes, Blake “did not see the enslavement of Africans as an aberration from or an affront to British values, but inherent in Britain’s materialist and warlike character, and its confinement to a narrow view of the world.” From marriage as enslavement in Visions of the Daughters of Albion to the wage slavery of the workshops and factories, Blake saw chains and bonds all around him, with only a few means of escape.

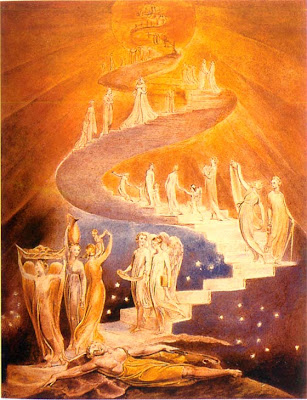

William Blake, The Resurrection of the Dead, Alternative design for a title page to Robert Blair’s The Grave, 1806; Pen and watercolor; 425 x 310 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

William Blake, The Resurrection of the Dead, Alternative design for a title page to Robert Blair’s The Grave, 1806; Pen and watercolor; 425 x 310 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

One means of escape Blake offers is through physical death, freedom from the material body. In an unpublished design to Robert Blair’s The Grave (above), Blake places us at the resurrection, showing several figures freshly freed from their chains and rising to heaven. Another means Blake offers is through the imagination, freedom from mental enslavement, specifically from classical culture and its materialism and martial spirit. John Milton, Blake’s poetic hero, emerges in Milton, a Poem as a savior from this cultural oppression. “For Blake, Britain in the early nineteenth century was still a country mentally enslaved by the material powers of nature, war and false art, with only a few artists keeping alive a vision of a better world,” Bindman writes. To combat this cultural blindness, Blake offers his unique vision of a society based on the imagination and spirit rather than the worldly concerns of the Greeks and Romans. Pinckney’s supporting essay on Equiano concentrates on some of this blindness, even in the case of the abolitionists. “Clarkson wrote his history of abolition as a contest between white men” arguing over laws, Pinckney writes. “Equiano wrote his history of himself as his battle for a free life among white men.” This transcendent vision, capable of seeing beyond the cultural ties that bind (which, again, Kara Walker employs in her own work), offers a possible solution to today’s international situation, especially in the context of terrorism, religious fanaticism, and open-ended warfare. When we all give up our bonds of fearfulness, nothing remains to be feared.

William Blake, Los with skeleton in chains, Plate 10 from The First Book of Urizen, copy D, 1794; Relief etching color printed with hand coloring; 151 x 109 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

William Blake, Los with skeleton in chains, Plate 10 from The First Book of Urizen, copy D, 1794; Relief etching color printed with hand coloring; 151 x 109 mm; Department of Prints & Drawings, The British Museum. Photo: © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

Blake’s poetry and art dramatize the power of desire like that of few others. His character Los stands as the eternal artist, yearning to be free to create. Placing Los in chains next to a skeleton representing death (above), Blake neatly encapsulates the true cost of all forms of enslavement—a death of the spirit as well of the body. In commemorating the bicentennial of the abolition of the British transatlantic slave trade, this exhibition of Blake’s work shows just how important that step was at the same time it shows how marginally incremental it also was. Another thirty years would pass before slavery would be banned in the British colonies, proving that the roots of slavery ran deep in the English soul. With these beautifully reproduced designs by Blake for his own poetry and that of others, this catalogue reminds us of the relevance of Blake’s vision not only for his own time but for our own. Blake, the poet and painter of Urizen and Los, is also the poet and painter of the dark London streets. We walk in his footsteps centuries later without realizing it, as enslaved by our culture as his contemporaries. Whether we recognize and break our chains remains up to us.

[Many thanks to The Hayward Gallery for providing me with a review copy of Mind-forg’d Mancles: William Blake and Slavery and for the images from the exhibition.]

UPDATE: Welcome Guardian Books Blog readers! In Ben Myers' post on Blake today, he links to this post above, posted just hours before. Just click on "poetry and art" in Ben's post and you'll find me. Nothing like the speed and reach of the internet, huh?

+1794.jpg)