When contemporaries looked at the paintings of Winslow Homer, they imagined the artist as a rugged outdoorsman, a man who knew the hunting scenes he captured so beautifully first hand. Born February 24, 1836, Homer often disappointed those who met him with his bank clerk exterior, the complete opposite of the action hero they pictured. Although he painted many works of sharpshooters and soldiers at rest during his time as an artist-correspondent in the American Civil War, Homer’s most famous Civil War image may be The Veteran in a New Field (above, from 1865), in which a soldier freshly returned home immediately throws off his uniform and picks up the scythe in his fervent desire for a return to normalcy. Despite that change of scenery, the taint of death remains in the act of mowing down the grass, which mimics the grim reaper mowing down lives in the war. Homer often suffers under the label of “illustrator,” as if he simply reported the facts and nothing else. In works such as The Veteran in a New Field, Homer presents the facts and much, much more. "I looked through one of [a sharpshooter’s] rifles once,” Homer wrote to a friend years after the war. “The impression struck me as being as near murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army and I always had a horror of that branch of the service." Homer’s images of war, even when at rest, never lose that sense of horror, however faint.

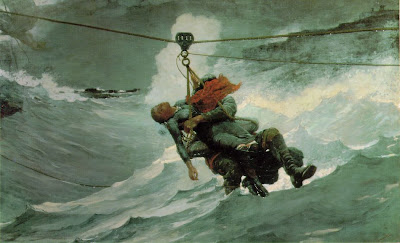

I’ve always found Homer’s work fascinating for its balance of commercialism and artistry. Homer always kept an eye on public tastes, filling it first with his Civil War works and later with more domestic scenes after the war. The image of the small town full of good people and children playing happily embedded in the late nineteenth century American consciousness owes much to Homer’s work. In a way, he filled the need of the country, coming to the emotional rescue of a nation longing for peace. Peace, however, failed to fill Homer’s own artistic need for drama and tension. While living on the rocky coast of Maine, Homer watched the daily drama of men and women battling the sea. The Life Line (above, from 1884) shows a man rescuing a woman from the deadly pull of the ocean. The woman’s wet clothes cling scandalously to her body. A red scarf obscures the face of the rescuer at the same time that it draws the viewer’s eye to the center of the painting. Even the straining ropes securing their lives speak of the tension of this scene. Nature itself seems to conspire against the pair in an image that encapsulates the conflict between humanity and nature.

Homer paints that conflict between humanity and nature even more nakedly in The Gulf Stream (above, from 1899). I’ve seen The Veteran and The Gulf Stream at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and marveled at the impact those individual figures have against their respective backdrops. Whereas The Veteran navigates a sea of grass, the lone sailor of The Gulf Stream pilots his way through the shark-infested waters of the Bahamas, which Homer visited in the late 1890s. Both men find themselves at risk of being devoured by death—the veteran through his memories of war and the sailor through actual physical peril. Homer apparently reworked The Gulf Stream many times, adding the tiny ship in the far distance that appears in the top left corner ever so faintly. After a lifetime of witnessing death and destruction, Homer may easily have fallen prey to a moment of despair, but he ultimately allows a small glimmer of hope of rescue against all the odds.

1 comment:

Great piece. Thank you for reminding me how much I like Winslow Homer's work.

Post a Comment