After studying the law and practicing for some time as a lawyer, as his father wished, Pierre Bonnard finally put the art classes he had been taking on the side to use and decided to become an artist. Born October 3, 1867, Bonnard searched for his big break, which came in 1899 when he received the commission to design a poster for France-Champagne (above). Bonnard’s Japonisme-influenced depiction of bubbly effervescently teeming over the brim of the glass captured the imagination of a generation of French graphic artists, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who mimicked Bonnard’s style and became Bonnard’s friend in 1891. With the money he made from this poster, Bonnard finally quit his law job and became a full-time artist. “Our generation always sought to link art with life,” Bonnard said years later. “At that time, I personally envisaged a popular art that had everyday applications.” Bonnard’s calligraphic lines with their flowing movement helped usher in the age of Art Nouveau, which dreamed of bringing art into every facet of everyday life.

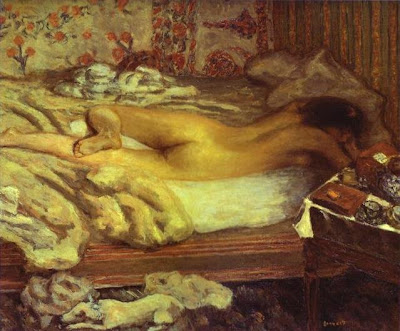

Bonnard interacted with many of the Impressionists of his day. Siesta (above, from 1899), one of many paintings in which Bonnard used his young wife as a model, shows the influence of Edgar Degas and his treatment of the female form. Bonnard helped found the group Les Nabis in the 1890s. Following the philosophy of Paul Gauguin if not Gauguin’s specific technique, Bonnard and others looked to infuse the subjects of Impressionism, such as the female nude, with a sense of spirituality and awe. In works such as Siesta and Indolence (also 1899), Bonnard transforms the nude female body into a religious artifact, literally pulsating with energetic color. The same primal force Gauguin found in the woman of the islands Bonnard found in the women of France, specifically his beloved wife.

In 1926, Bonnard moved to the French Riviera, where he remained for the rest of his life. Works such as Landing Stage (above, from 1938-1939) show Bonnard’s love for the blue skies and water of the Riviera—the blue that Henri Matisse claimed he had been searching for all his life. Although Bonnard opened up his palette to a whole new world of color, he never embraced Fauvism or any other new art movement of the first half of the twentieth century. Bonnard carried on in his personalized Post-Impressionist fashion until his death in 1947, five years after the passing of his beloved wife. It’s hard to think of Impressionism stretching past the horror of Nazism and World War II, but Bonnard outlived even those movements in history. Like a fine bottle of champagne, Bonnard kept bubbling along and never stopped being the life of the party.

1 comment:

Happy to find a good art blog...the are so rare.

Thanks for sharing....

Great work.

Post a Comment