George Bellows. Introducing Georges Carpentier, July 1921. Crayon with touches of pale brown wash on smooth, dark cream, wove one ply card stock. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

George Bellows. Introducing Georges Carpentier, July 1921. Crayon with touches of pale brown wash on smooth, dark cream, wove one ply card stock. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.On July 2, 1921, French boxing champion and World War I hero Georges Carpentier squared off against American Jack Dempsey, whom the American crowd booed as a “draft dodger” for not fighting in the war. George Bellows, the great American illustrator known best for his boxing images, sat in the crowd and chose to depict the moment (above) when the American crowd cheered the Frenchman as Dempsey sat in his corner getting his hands taped up to knock Carpentier out in the fourth round. In the current exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Art, The Powerful Hand of George Bellows: Drawings from the Boston Public Library, we see George Bellows not just as the painter of athletes but as a truly diverse artist who captured the entire American scene with a technical proficiency in printmaking and lithography few other American artists could match in the first half of the twentieth century.

+1915.jpg) George Bellows. Preaching (Billy Sunday), March 1915. Crayon, pen and ink, brush and ink wash on paper. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

George Bellows. Preaching (Billy Sunday), March 1915. Crayon, pen and ink, brush and ink wash on paper. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.Robert Conway, curator of the exhibition, examines Bellows’ career as a graphic artist in an exhaustive essay to the catalogue. Conway sees Bellows pursuing parallel careers as a painter and an illustrator, a path many of the Ashcan School artists took not only to pay the bills but also to fulfill their ideological quest to bridge “the artificial separation between the concerns of fine art and the subject matter of popular culture.” Thanks to the diversity of the Wiggin Collection at the Boston Public Library, this exhibition traces the evolution of many of the images from initial drawing to finished print, showing that Bellows often resurrected drawings from years before to use as print subjects. Still, many of Bellows’ drawings came from current events thanks to his work for newspapers, such as Preaching (Billy Sunday) (above). In January 1915, Bellows traveled to Philadelphia with journalist John Reed to cover Sunday’s “Christ for Philadelphia—Philadelphia for Christ” rally. Bellows captures Sunday at the height of action, almost leaping upon the rapt crowd beneath his pulpit. In contrast to the almost sinister Sunday, Bellows draws the faces of the crowd in a cartoonish, caricature style. “I like to paint Billy Sunday, not because I like him, but because I want to show the world what I do think of him,” Bellows later said. “Do you know, I believe Billy Sunday is the worst thing that ever happened to America? He is death to imagination, to spirituality, to art… His whole purpose is to force authority against beauty.” Such “reactionary” behavior by Sunday, Bellows claimed, forced him to be an “anarchist” in his art in order to save America and art itself from Sunday’s influence. In such works, Bellows rises to the order of Hogarth or Goya in terms of social content in a single striking image.

George Bellows. The Barricade, 1918. Crayon, varnished, on Strathmore Drawing Board. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

George Bellows. The Barricade, 1918. Crayon, varnished, on Strathmore Drawing Board. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

Conway condemns Bellows for allowing his “facility” overcome his “anarchist” tendencies too often. Bellows’ “engaging touch of humor kept him skating across the surface of the world he illustrated, only rarely digging into its substance… Unlike Goya, Hogarth, and Daumier, his distinguished predecessors, Bellows did not invest his satirical illustrations with the strength of his convictions.” I felt that Conway asked too much of works by Bellows made with clear humorous intent, misreading the Ashcan School philosophy of playfulness and pleasure-seeking so wonderfully examined in the Detroit Institute of Arts’ recent exhibition and catalogue Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush with Leisure, 1895-1925 (reviewed here). Conway, however, does credit Bellows with courageousness in his series illustrating the German World War I atrocities in Belgium, including The Barricade (above), which shows German soldiers using innocent civilians as human shields. Conway tempers even that praise with criticism of the artfulness of the image, seeing Bellows’ use of the compositional theory known as “Dynamic Symmetry” as hindering Bellows’ natural gift for composition. Bellows believed “Dynamic Symmetry” to be “as profound as the law of the lever or the law of gravitation,” but Conway rightfully sees it as a self-imposed obstacle.

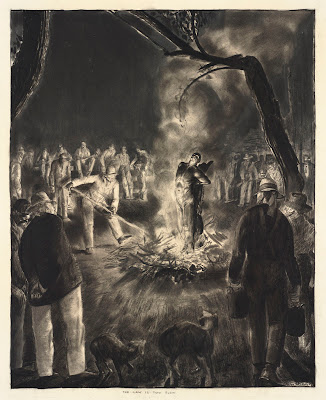

George Bellows. The Law Is Too Slow, Winter 1922-1923. Crayon on smooth, cream-colored, thick, wove paper, most likely Strathmore Drawing Board. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

George Bellows. The Law Is Too Slow, Winter 1922-1923. Crayon on smooth, cream-colored, thick, wove paper, most likely Strathmore Drawing Board. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

Fortunately, over time, Bellows slowly slipped from under the influence of “Dynamic Symmetry” and allowed himself to follow his usually impeccable instincts. Through it all, Bellows “never lost his instinct for the right choice,” Conway writes. Perhaps the most strikingly “right” choice from the collection comes in the work The Law Is Too Slow (above), which depicts a vigilante killing in the 1920s, an all too familiar scene as the Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence within America. The central burning figure recalls the white-shirted man of Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 in its eye-arresting brilliance. The blood-thirsty crowd seems almost inhuman in their rough features as nature itself, in the form of the dark tree dominating the background, appears twisted by the injustice of their actions. Bellows’ personal thirst for justice comes through in the two-way title, which can be read as the rationale of the killers for taking justice into their own hands or as the lament of right-thinking people who mourn the death of an innocent man based solely on skin color.

George Bellows. Girl Sewing, Winter 1923. Crayon on lightweight cream wove paper. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

George Bellows. Girl Sewing, Winter 1923. Crayon on lightweight cream wove paper. Wiggin Collection, Boston Public Library.

What makes the depictions of violence and injustice all the more striking are Bellows’ depictions of the joys of a simple home life, such as Girl Sewing (above), a portrait of his wife Emma. “You would not call him very affectionate,” a personal friend said of Bellows, “but he had a great deal of affection bottled up in him.” Such affection bubbles up in his drawings of his family, particularly of his children. Bellows died in 1925, only 43 years old, leaving behind a tantalizing glimpse of how much more he could have accomplished. The Powerful Hand of George Bellows demonstrates the technical prowess of Bellows as well as the complex mind and heart that guided that hand. In the Wiggins Collection, works by Durer, Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier, de Toulouse-Lautrec, and others rightfully take pride of place, but this exhibition and catalogue prove that George Bellows could stand toe to toe with any of them.

[Many thanks to the San Antonio Museum of Art for providing me with a review copy of The Powerful Hand of George Bellows: Drawings from the Boston Public Library and for the images above.]

No comments:

Post a Comment